In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

E.E. “Doc” Smith was a seminal figure in the early days of science fiction. While he is best known for his long-running Lensman and Skylark series, his second book, Spacehounds of IPC, is worthy of note. It is a standalone adventure that features a couple’s struggle for survival after the spaceship they are traveling on is cut apart by mysterious aliens from the planet Jupiter. Their adventures take them to Jupiter’s moon Ganymede to a fictional comet, then on to Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, and then to a series of massive space battles. And if you are not familiar with Smith’s fiction, this novel is a good example of the best (and worst) aspects of his work.

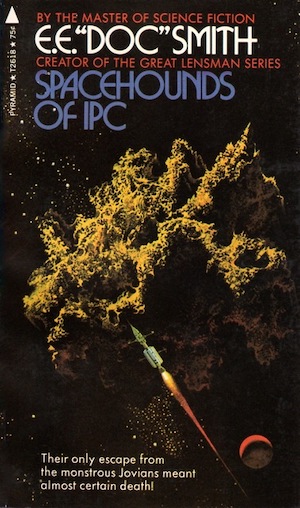

Spacehounds of IPC first appeared in the magazine Amazing Stories in 1931, and was published in book form by Fantasy Press in 1947. The copy of Spacehounds of IPC I used for this review is a paperback reissue from Pyramid books, a third printing from December 1973. The cover is definitely a product of the ’70s, with a white cover and a trippy shadowed geometric sans-serif font, but a fairly generic cover painting of a spaceship near a generic looking rocky body in space. The uncredited painting lacks the energy of the impressionistic paintings by Jack Gaughan that graced the covers of most of Pyramid’s other Doc Smith reprints.

According to his biography on Wikipedia, Smith was very pleased with Spacehounds of IPC, hoped it would be the start of a series, and thought it was one of his best works, grounded in real science, not in pseudo-science. But readers reportedly did not like the fact that the action in the novel was contained within our solar system, and when Harry Bates, editor of Astounding, made a lucrative offer to Smith to write an adventure with less science and more action, Smith turned in Triplanetary, and the lurid but exciting Lensman series was born (although, due to financial issues, Triplanetary ended up being published in Amazing, and not Astounding).

About the Author

Edward Elmer Smith (1890-1965), often referred to as the “Father of Space Opera,” wrote under the pen name E.E. “Doc” Smith. I included a complete biography in my review of Triplanetary. Doc Smith’s first book was The Skylark of Space, which eventually lead to a series that included Skylark Three, Skylark of Valeron, and Skylark DuQuesne. Doc Smith is best known for his epic Lensman series, which including Triplanetary, First Lensman, Galactic Patrol, Gray Lensman, Second Stage Lensmen, Children of the Lens, and Masters of the Vortex.

Hits and Misses

After discovering that Smith felt Spacehounds of IPC was his most realistic work, I decided it would be worth a read. While I enjoyed his other books, from my perspective a little more realism would be a welcome change. But I was surprised when the back cover described a space liner being cut to pieces by “lethal scissors of light,” and the front piece describing a young woman being overcome by the perfume of a gigantic malevolent flower, and in danger of being “devoured alive!” And as I started reading the book, I realized that being more realistic than the Lensman and Skylark series still left a lot of room for pulpy excess. There is a lot of questionable science here, but also some accurate predictions, and it is interesting to examine Smith’s hits and misses.

The first thing a reader will notice is a number of anachronisms in the language Smith uses. In this narrative, “computers” are people who do math, not the “calculating machines” they use for the math. We now think of “dirigibles” as powered lighter-than-air craft, but the term is short for dirigible airship, with dirigible being a term for “steerable.” So, when Smith uses the term dirigible for a directional antenna or weapon, he is talking about it being aimed, not flying through the air. And it turns out to be far easier (in reality) to communicate across space than Smith and his contemporaries thought it would be. Almost no one still uses Morse Code to communicate, as the characters in the book do. (The term “fist,” by the way, refers to the individual accent or rhythm someone has when tapping a telegraph key, kind of like an accent when speaking, something I remember from my own days at sea many years ago.) One thing that does stand out is the goofy slang characters use when bantering with each other, something I will point out is not an anachronism, but seems to be Smith’s idea of wit. To the best of my knowledge, even back in the early 20th century, people didn’t talk like that.

The space travel Smith describes is based on early ideas of the power of electricity, many of which did not pan out in the real world. Smith’s ships have massive storage batteries called accumulators, which are charged by power beamed from power plants on Earth, which has limited human travel to the inner system. Smith posits that electricity can be used not just to generate magnetic fields, but also to power pressor and tractor beams that can push and pull ships through the ether (and “ether” does not seem to be just a figure of speech here). The ships are armored, as the threat of meteorites was overestimated by scientists of the day. The force beams and force fields Smith describes being used in combat remain figments of imagination.

Smith did not stick with the consensus of science fiction authors in his day regarding the planets and moons of our solar system. His most accurate predictions were in the gravity of each body. He was more pessimistic about Mars and Venus than many of his contemporaries, seeing both planets as being uninhabitable by humans without protective gear. On the other hand, he saw Ganymede as having a shirtsleeve environment, with a thinner atmosphere whose higher oxygen content made it breathable. Jupiter was seen as cloudy like Venus. Saturn was also seen as a shirtsleeve environment for humans, with only a hint of sulfur compounds in the atmosphere making it unpleasant. Smith’s most realistic prediction was for Titan, which he imagined as cold enough that ice would be a building material, and hydrocarbon-based gasses would be liquids. And his description of a comet was not too far off from current science.

Smith saw a solar system filled with living creatures, with human-like creatures as the apex of creation. He portrayed scientists as arguing whether this was due to common ancestry, or parallel evolution, a theory common at the time that evolution would produce similar results regardless of location. He depicted his Venusians, Martians, and inhabitants of the Jovian moons as having generally human characteristics. His six-limbed Hexans were designed to be an unsympathetic threat, and he invented some other interesting alien beings. His most interesting human creatures were the Titanians, who were adapted to extremely cold conditions, and whose chemical composition was driven by those cold temperatures, but who were ironically the most empathetic of the intelligent creatures of the solar system.

In terms of social predictions, Smith was not terribly imaginative. The story is dominated by male characters, although there is a female protagonist who is plucky and resourceful, not just there to be a love interest. He did state in passing that his Inter-Planetary Corporation had discovered how to construct atomic bombs, and used that knowledge to bring peace to the Earth, a statement that raises more questions with me than it answers.

All in all, while much of the scientific extrapolation used by Smith has turned out to be rather preposterous, he does a good job of playing consistently with the rules he had established within the story. This rigor and attention to detail did make the narrative more compelling, as the characters worked to find scientific solutions to the various challenges they faced.

Spacehounds of IPC

Noted computer Doctor Percival “Steve” Stevens boards Inter-Planetary Vessel (IPV) Arcturus, a venerable passenger vessel, for what should be a routine voyage. Vessels have been having difficulties with navigation, and he soon finds the problem lies in the guidance given by space stations that are sloppy about keeping their positions. He is then asked to give a tour of the vessel to Nadia Newton, daughter of the head of the Inter-Planetary Corporation, or IPC. Expecting to meet with a child, he is delighted to find she is a beautiful young woman. While Nadia is extremely capable and intelligent, her lack of scientific knowledge gives Smith a chance to explain to her (and also to the readers) how the space vessels in the story work. But while they are touring engineering spaces, Arcturus comes under attack from mysterious aliens, whose force beams slice the vessel into chunks, which the aliens take into tow using tractor beams (the first time the term “tractor beam” was used in science fiction).

Fortunately for Steve and Nadia, the section they are in contains a number of lifeboats and quite a bit of useful machinery. Steve sets out to cobble together the systems they have available into a working spaceship, which they dub the Forlorn Hope. As the alien ship nears the moon Ganymede, they are able to trigger explosions in the wreckage that cover their escape, and they land on the moon, finding a rocky chasm near a waterfall to use as a hiding place.

Smith loved to describe scientists at work, and what follows is one of the most interesting parts of the book for me, as Steve works to build a hydroelectric generator in the waterfall, along with a power transmitter that can charge the accumulators of their ship and allow them to call for help, and possibly even escape. This is the work of many months, as Steve often not only has to construct the various devices, but also fabricate the tools he needs for those tasks. Nadia works to keep the two of them clothed and fed, which is no small task, as it involves hunting local wildlife with a homemade bow and arrow. Fortunately, the two of them are physically fit (he was a champion diver, and she a champion golfer), and their struggle to survive makes them even tougher. Steve has a crisis in confidence, and confesses he has fallen in love with Nadia, and his need to keep her safe is weighing on him. Nadia returns that affection, and they decide to become engaged, with a wedding once they return to civilization. That might seem strangely chaste to modern readers, but editors of the time frowned upon depictions of extramarital sex, even among castaways.

One day, Nadia shoots an animal she has not yet encountered, a six-limbed red creature (later dubbed a Hexan), and having only wounded it, follows it far from their camp. She finally kills it, but falls victim to a carnivorous and ambulatory plant that carries her away. Steve, realizing she has been gone for a while, dons a spacesuit he has reinforced with armor, and goes out with bow, sword and dirk to find her. He catches up with the malevolent plant, and slays it in an epic and brutal fight. They kill another of the Hexans as they return to their camp.

Steve needs heavier metals than are available on Ganymede to build a transmitter, and decides they should try to fly to a comet that should be in the vicinity of Jupiter. But while they are preparing to leave, they are attacked by more Hexans, who turn out to be a primitive intelligent species. That gives Steve another chance to use his armored suit and sword, backed up by Nadia’s archery skills. They slaughter the attackers, and as they take off for their comet, pause in midair to blast away even more Hexans (Smith’s tendency to slaughter enemies without regret shows even in this early work).

While Steve and Nadia are gathering what they need from the comet, another Jovian vessel attacks them, and starts chopping up their already jury-rigged ship. But in the nick of time, they are rescued by strange humans from Saturn’s moon Titan, who have been clashing with the Jovians. The Titanians tow them to their moon, and repair their ship. Our heroes are able to help the Titanians fix one of their powerplants, built on Saturn, an environment hellishly hot for the Titanians, but comfortable for the Terrans. They fly their rejuvenated Forlorn Hope back to Ganymede, finish their transmitter, and call for help, a call soon answered by Steve’s fellow computers on the science vessel IPV Sirius. And those scientists, who include the volatile Brandon and the shy Westfall, immediately begin working on not only duplicating the devices and weapons of the Jovians, but also countermeasures.

Smith then shifts the viewpoint to the previously unknown human inhabitants of the Jovian moons, driven underground by the intelligent and malevolent Hexans of Jupiter. These Hexans are cousins to the savage Hexans that Steve and Nadia encountered on Ganymede, and are irredeemably hostile and evil, giving Smith’s protagonists a foe they can exterminate without guilt. The Jovian humans have found and rescued the remaining survivors from IPV Arcturus. And we are also introduced to Vorkulians, a race of flying reptiles who are at perpetual war with Jupiter’s Hexans. Soon, there is an open war between all factions for domination of the Jupiter system. This clash is interesting because it is not just mindless combat; instead, it is a struggle of scientific knowledge, and advances in technology, a theme that Smith addresses with gusto. While Steve and Nadia are almost completely set to the side in this struggle, it still brings the book to an entertaining conclusion.

Final Thoughts

Spacehounds of IPC is often overlooked by those who study the work of Doc Smith, but I think it is my favorite of his books. It stands alone, without a need for prequels or sequels. It is an engaging adventure with compelling characters, and interesting (although dated) scientific extrapolation. If you haven’t read any of Smith’s books, and are curious about early science fiction and space opera, this is certainly an entertaining starting point.

And now it’s your turn to chime in. I look forward to hearing your thoughts on this book, on Smith’s other work, or on the topic of space opera in general.

“Almost no one still uses Morse Code to communicate, as the characters in the book do.”

True, but Morse is a binary code, and any digital communication is binary.

;-)

Morse code has dots and dashes, but there are also short and long pauses between the dots and dashes, so I don’t think that counts as binary.

So, Greedo did not shoot first?

Smith’s characters frequently shoot first, and think later. In this case, Nadia triggers open warfare with an intelligent species. She and Steve only survive by being better at slaughter than the hexans.

That’s a great point about the meaning of dirigible. It never occured to me that Smith would use it in the sense of being able to be directed.

I get a kick out of seeing which things taken for granted in SF (like force fields and tractor beams) show up first in Smith.

I think James Blish likewise described a world with spindizzies mounted as a “dirigible planet” in the Cities in Flight books.

Dirigible::direct as eligible:elect; I’m not sure if there are other words that follow the pattern. (It also means that blimps are technically dirigible airships, even though there term is in practice limited to rigid-framed models.)

I always wanted to think of this as a pre-Triplanetary book in the Lensman universe, but the technology and timeline and some of the alien species don’t quite work out.

I quite liked the Vorkulians, who were a nice break from the humanoid=good nonhumanoid=evil paradigm.

Applying the term “computer” to humans who do math and calculations may in fact not be quite as anachronistic. NASA, for example, employed human computers – many of them highly gifted African-American women – as late as in the early 1960s in the nascent space program, as also depicted in the book and movie Hidden Figures (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Computer_%28occupation%29 ).